Jari Kaivo-oja:

Hesiod and Hypnos

Hypnos (Greek word: Ὕπνος) was the personification of a dream in Greek mythology, the Roman equivalent of which was Somnus. He was the twin brother of Nyks, the night, and Erebos, darkness, and of Thanatos, death. Hypnos is depicted in ancient art as either a naked young man with wings on the temples or a bearded man with wings on his shoulders.

Greet poet Hesiod, a Greek poet who wrote about Hypnos and his role in Greek mythology in his epic poem “the Birth of the Gods” (Θεογονία, Theogonia), describing the ancestry and lineages of the gods in Greek mythology. The poem comprises 1,020 verses. The literary form of the Birth of the Gods became established in the 500s before the dawn of time. At that time, new parts were added to the poem, such as verses 901–1020 at the end of the classic poem. Traditions continued to develop even after the work of Hesiod.

However, the work of Hesiod has often been used as a reference work for Greek mythology. Hesiod is generally regarded by Western authors as the first written poet in the Western tradition to regard himself as an individual persona with an active role to play in his subject. We can easily find the relevance of this special topic in the actor-network theory of foresight. Among other things, Herodotus considered Hesiod an authority regarding the names of the gods and their attributes (Herodotos: Historiateos II.53, Herodotus 1993).

From the historical perspective, Hesiod should be referred to as a basic fundamental source of narrative storytelling in the fields of foresight and anticipation. Abductive reasoning (also called abduction, abductive inference, or retroduction) is an elementary issue in storytelling and narrative thinking, and it is a form of logical inference that seeks the simplest and most likely conclusion from a set of observations. Abductive reasoning was formulated and advanced by American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce beginning in the last third of the 19th century (see good motivation of this issue in Peabody 1975. Josephson & Josephson 1994, Peirce 1998, Walton 2001, Carson 2009, Milojević & Inayatullah 2015, Syll 2023).

In the of economic thought, Hesiod can be seen as a central source of thinking before Adam Smith and some scholars keep Hesiod as a father of humanistic economics (see Brockway 2001, Gordon 1975).

Futures dialogues, future-oriented dreams, and visions can be defined to be forms of socio-therapy

Quality of sleep has a very significant impact on human thinking, as sleep is essential for brain function and cognitive performance. During normal sleep, the brain (1) consolidates memories, (2) processes information, and (3) repairs itself. When we don’t get enough good quality sleep, our cognitive performance can suffer in various ways. For example, our ability to focus, pay attention, and concentrate can be impaired. We may also experience memory problems and have difficulty learning and retaining new information. Research has shown that sleep deprivation can also negatively affect our mood and emotions, causing us to feel irritable, anxious, and depressed. In addition, lack of sleep can compromise our decision-making ability, judgment, and creativity. On the other hand, getting enough high-quality sleep has been shown to enhance cognitive performance, improve memory consolidation, and enhance overall brain function. (see e.g. Walker 2017, Nelson et al. 2022). Quality of sleep is thus very important for human creativity and human understanding.

We should also see the importance of dialogue as a form of socio-therapy. Futurists are creating all kinds of dialogues and from this perspective, we should understand in a better way that these dialogues can be interpreted to be a form of socio-therapy (see Bohm & Edwards 1991, Bohm 1992). Only a few futurists understand their societal role as socio-therapists.

Hypnos and dialogical narratives

Greek mythology can often be seen as a starting point for dialogical narratives. In the context of foresight and qualitative anticipative storytelling research, one can always lean on classic stories and myths. Greek mythologies can be associated with basic human problems, challenges, and humanism.

There are many good reasons to analyze Hypnos and Hypnos´s relation to foresight and anticipation research. According to some sources, the personifications of dreams, thousands of oneiros, would be descendants of Hypnos, but they are reported in older sources to be descended directly from Nyks (Hesiod, trans. 1914). Among them is mentioned as Morpheus, who announced prophecies in dreams, both Fobetor and Fantasos, which were sources of false visions and dreams. (See Ovid Books, 1922). Thus, Hesiod can be linked also to the pre-history of visionary thinking, foresight, and anticipation.

The ability to dream is not a self-evident issue

In many ways, Hypnos symbolizes the importance of dreams for people and their decision-making. The ability to dream is strongly associated with dreams and their quality. Sleep is crucial for our brain’s cognitive functions, including memory consolidation and problem-solving. Getting enough restful sleep can enhance our ability to think creatively and solve problems, which can lead to more visionary thinking during our waking hours. Dreams and sleep are important components of visionary thinking because they allow our minds to explore and imagine beyond the constraints of our waking reality.

Dreams and sleep are closely connected to visionary thinking because they allow our minds to enter a state of creativity and imagination that is often difficult to access during our waking hours. Normally, during the dreaming phase of sleep, our brains are highly active, and we are able to create vivid and often surreal experiences that can be interpreted as a form of visionary thinking. Dreams can be a source of inspiration for artists, writers, other creative artists, and scientists, as they often contain imagery and themes that are both symbolic and deeply personal.

Hypnos, the legacy of foresight research, and anticipation theory

Anticipation and foresight are closely related concepts, but there are some key differences between them. Very often these concepts remain undefined and are seen as the same things.

Normally, anticipation refers to the act of expecting or predicting something to happen in the future. It involves recognizing a future event and making plans or preparations based on that expectation. Anticipation can be based on past experiences, current trends or patterns, or intuition.

On the other hand, foresight activities involve a deeper level of thinking about the future. Foresight involves considering multiple potential scenarios, analyzing the potential consequences of each, and making strategic plans to prepare for those possibilities. The “fully-fledged foresight” includes the choice of foresight methods, networking and stakeholder analyses, and models of decision-making. Foresight requires a broader perspective and a willingness to consider multiple perspectives and possibilities. It requires also a basic understanding of stakeholders and networks and decision-making criteria. The choice of foresight methods can be based on the FAROUT criteria (future orientation, accuracy, resources, objectivity, usefulness, and timelines).

Perfect rationality, imperfect rationality, problematical rationality, or irrationality?

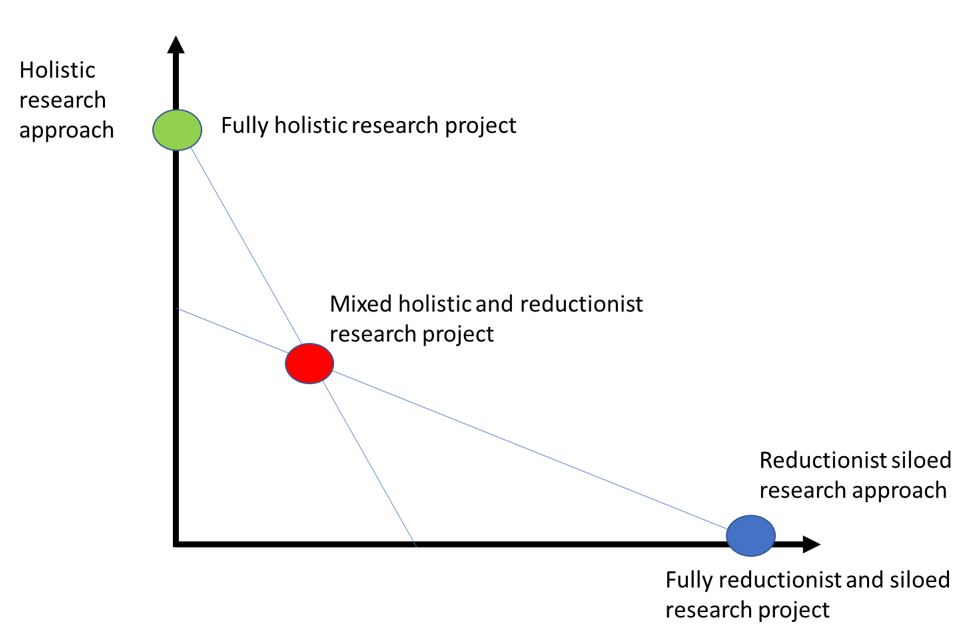

In other words, anticipation is more reactive, and focused on a specific event or outcome, while foresight is proactive, and focused on anticipating and planning for a range of possible outcomes and their consequences. This critical difference leads logically to different relations to the Hypnos issue and especially to visionary thinking and leadership. Actually, it may be not easy to be very visionary, if we are focused only on a specific issue or event. As noted by Robert K. Merton Professor of Social Sciences (Jon Elster 1978, 1979) there is a descending sequence from perfect rationality, through imperfect and problematical rationality, to irrationality in human thinking. Rational explanation is not the same analogous thing as understanding a thing or phenomenon. We have seen many very problematic examples of siloed anticipation studies where a potential balance between reductionist and holistic thinking is not much questioned or less critically discussed (see updated discussion of Anderson 2022, Jackson 2019).

In Figure 1 we can observe three basic scientific approaches: the fully holistic research approach, the mixed holistic and reductionist approach, and the fully reductionist approach. All futures researchers (and maybe all others researchers too) should be aware of these three basic methodological alternatives.

Figure 1. A holistic research approach and a reductionist research approach.

We should always define, whether are we going to explain or understand human behavior because these two human activities are different activities and lead us to different methodological choices. A holistic research approach typically supports understanding phenomena, but a reductionist approach may help in explaining phenomena. Boundaries between these methodological approaches (solutions) are not always very clear and there are also boundary options (mixed holistic and reductionist approaches).

In the future, we may be more visionary with “fully-fledged three foresight pillars” of methods, network analyses, and decision-making models. As many times noted in various scientific discussions, a loss of one or two foresight research pillars leads surely to an unsuccessful foresight process. A deep understanding of methodological choices, network/stakeholder context, and decision-making model with decision criteria, is surely needed for a successful foresight process.

To summarize, anticipation is about predicting a specific outcome and taking action to prepare for it, while foresight involves a more comprehensive and strategic approach to planning for the future, considering multiple possibilities and their potential consequences. Hopefully, our bright and dark journeys in the Hypnos world will lead us to think about many alternatives, even surprising options, wild card scenarios, and not business-as-usual alternatives.

Unfortunately, Business-As-Usual (BAU) scenarios often dominate siloed and highly theoretical and siloed anticipation studies. It is good to be aware that whenever we abandon the use of many perspectives in the context of future-oriented research, we do not make use of holistic thinking and end up with siloed reductionist studies.

The most low-quality foresight research is to present the BAU scenario and almost identical other scenarios as supposedly alternative scenarios. I have noticed these kinds of problematic methodological issues in the context of several foresight studies (see for example, Kaivo-oja, Keskinen & Rubin 1997, Kaivo-oja, Rubin & Keskinen 1998).

Jari Kaivo-oja

Research Director, PhD, Finland Futures Research Centre, Turku School of Economics, University of Turku;

Adjunct Professor (University of Helsinki, University of Lapland, and University of Vaasa);

Professor (Social Sciences), Kazimiero Simonavičiaus University, Vilnius, Lithuania

References and background literature

Anderson, Monica (2022) The Red Pill of Machine Learning. Experimental Epistemology. Web:

Bohm, David & Edwards, Mark (1991) Changing Consciousness: Exploring the Hidden Source of the Social, Political, and Environmental Crises Facing Our World. HarperCollins. San Francisco.

Bohm, David (1992) Thought as a System. Routledge. London and New York.

Brockway, George P. (2001) The End of Economic Man: An Introduction to Humanistic Economics, 4th edition (2001), p. 128.

Carson, David (2009) The Abduction of Sherlock Holmes. International Journal of Police Science & Management. 11 (2), p. 193–202.

Dosi, Roberto (2017) Introduction to Anticipation Studies. Anticipation Science 1. Springer.

Elster, Jon (1978) Logic and Society. Contradictions and Possible Worlds. John Wiley & Sons. Chichester and New York,

Elster, Jon (1979) Ulysses and the Sirens: Studies in Rationality and Irrationality. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Evelyn-White, Hugh G. (1964) Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica. Loeb Classical Library, Vol. 57, Harvard University Press, Boston, USA.

Gordan, Barry J. (1975) Economic Analysis Before Adam Smith: Hesiod to Lessius (1975), First Edition, Basingstoke and London, p. 3.

Griffin, Jasper (1986) Greek Myth and Hesiod, in J. Boardman, J. Griffin and O. Murray (eds.), The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p. 88.

Hardie, Philip, Barchiesi, Alessandro, and Hinds, Stephen (1991) Ovidian Transformations: Essays on Ovid’s Metamorphoses and its Reception. Series: Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society Supplementary Volume. Volume: 23. Cambridge Philological Society,

Herodotos: Historiateos II.53

Herodotus (1993) Historiae. Volume II: Books V-IX. Third Edition. Edited by K. Hude. Oxford Classical Texts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle, Homerica. Translated by Evelyn-White, H G. Loeb Classical Library Volume 57. London: William Heinemann, 1914.

Inkinen, Sam & Kaivo-oja, Jari (2009) Understanding Innovation Dynamics. Aspects of Creative Processes, Foresight Strategies, Innovation Media and Innovation Ecosystems. Finland Futures Research Centre. Turku School of Economics. FFRC eBooks 9/2009. Turku.

Jackson, Michael J. (2019) Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity. Responsible Leadership for a Complex World. First Edition. John Wiley and Sons. UK and USA.

Josephson, John R. & Josephson, Susan G., (eds.) (1994) Abductive Inference: Computation, Philosophy, Technology. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK; New York.

Kaivo-oja, Jari (2017) Towards Better Participatory Processes in Technology Foresight: How to Link Participatory Foresight Research to the Methodological Machinery of Qualitative Research and Phenomenology? Futures, Volume 86, February 2017, p. 94–106.

Kaivo-oja, Jari, Keskinen, Auli & Rubin, Anita (1997) Eurooppa-selonteko ja tulevaisuudentutkimus [European reporting and futures research]. FUTURA, Vol. 16. No. 1, p. 6–15.

Kaivo-oja, Jari, Rubin, Anita & Keskinen, Auli (1998) Proaktiivisa toimijoita vai koekaniineita Euroopan tietoyhteiskuntalaboratoriossa? Lipposen hallituksen tulevaisuusselonteon kommentointia tulevaisuudentutkimuksen näkökulmasta [Proactive Actors or Guinea Pigs in the European Information Society Laboratory? Commenting on Lipponen’s Government Report on the Future from the Perspective of Futures Research]. Tulevaisuuden tutkimuskeskus. Turun kauppakorkeakoulu. FUTU-julkaisu 4/98, Turku.

Kaivo-oja, Jari & Roth, Steffen (2023) Strategic Foresight for Competitive Advantage: A Future-oriented Business and Competitive Analysis Techniques Selection Model. International Journal of Forensic Engineering and Management. Forthcoming. ©Inderscience Publishers.

Keenan, Michael, Loveridge, Dennis, Miles, Ian & Kaivo-oja, Jari (2003) Handbook of Knowledge Society Foresight. Prepared by PREST and FFRC for the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Final Report, Annex B, European Foundation. Dublin. Web:

Milojević, Ivana & Inayatullah, Sohail (2015) Narrative Foresight. Futures, Volume 73, October 2015, p. 151–162.

Moe, Sverre and Kaivo-oja, Jari (2018) Model Theory and Observing Systems. Notes on the Use of Models in Systems Research. Kybernetes, Vol. 47, Issue: 9, p. 1690–1703.

Nelson, Kathy L., Davis, Jean E. & Corbett, Cynthia F. (2022) Sleep Quality: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Nursing Forum. Vol. 57(1), p. 144–151.

Ovid (1922) Metamorphoses. Translated by More, Brookes. Boston, Cornhill Publishing Co.

Peabody, Berkley (1975) The Winged Word: A Study in the Technique of Ancient Greek Oral Composition as Seen Principally Through Hesiod’s Works and Days. State University of New York Press.

Peirce, Charles Sanders (1998) On the Logic of Drawing Ancient History from Documents. The Essential Peirce, Volume 2, Selected Philosophical Writings (1893-1913), Peirce Edition Project, Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, p. 107–9.

Rothbard, Murray N. (1995) Economic Thought Before Adam Smith: Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, vol. 1, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing (1995), p. 8;

Syll, Lars P. (2023) Deduction, Induction, and Abduction. In Jesper Jespersen, Victoria Chick, Bert Tieben (Eds.) Routledge Handbook of Macroeconomic Methodology. Routledge, London.

Walker, Matthew (2017) Why We Sleep. The New Science of Sleep and Dreams. Simon and Schuster Inc. New York, USA.

Walton, Douglas (2001) Abductive, Presumptive and Plausible Arguments. Informal Logic. Vol. 21 (2), p. 141–169.

West, Martin Litchfield (1966) Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Picture: Pixabay.com